by Shelagh Pizey-Allen

In January 2017, Toronto police officers were captured on video Tasering and kicking a person who was restrained and lying on the ground. One officer threatened to seize the video: “Stop recording or I’m going to seize your phone as evidence and then you’re going to lose your phone.” The same officer made HIV-phobic comments, telling the videographer: “He’s going to spit in your face, you’re going to get AIDS.” Following the incident, both the Toronto Police Service and the Toronto Police Association affirmed that the public has the right to record police, as long as they do not interfere with police work.

Yet many bystanders, journalists, and activists who record police activity have faced intimidation, seizure of their equipment, and even arrest. PEN Canada, an organization that advocates for freedom of expression, has documented high-profile cases in which police officers confiscated recording equipment or arrested journalists.

In the case of Robert Dziekanski, a Polish man who died after being Tasered by police in the Vancouver Airport, officers seized the video recording made by bystander Paul Pritchard. Pritchard later sued police, and after the video was returned it became clear that the RCMP had lied in their notes and statements about how their interactions with Dziekanski had unfolded. During the 2010 G20 summit in Toronto, a number of journalists covering the protests were detained, arrested, and assaulted, including journalists working for the Globe and Mail, CTV News, and the National Post.

Not included in PEN Canada’s list was a series of illegal camera seizures by Winnipeg police officers between 2005 and 2010. After a campaign by police accountability group Winnipeg Copwatch, the Manitoba Law Enforcement Review Agency recommended that the Winnipeg Police Service change their policy on recording equipment.

In a disturbing example of police targeting those who record their activities, the only person to face criminal charges related to the 2014 police killing of Eric Garner in New York City is Ramsey Orta, the person who captured Garner’s death on video. In the video, Garner can be heard saying “I can’t breathe.” Orta has since been arrested multiple times and says that police are deliberately targeting him for making the video public. Meanwhile, a grand jury did not indict the police officer who choked Garner.

Garner’s case and others like it, such as the police shooting of Sammy Yatim in Toronto, serve as a reminder that clear video evidence is not always sufficient to prove in court that murder or police violence has taken place. But in the court of public opinion and as political mobilization tools, video recordings of police remain essential.

Know your rights

The following list of resources from Canadian police accountability and media organizations focus on asserting your right to record the police in public. Some include tips for recording the police that can strengthen a video’s admissibility as evidence in court.

Photography

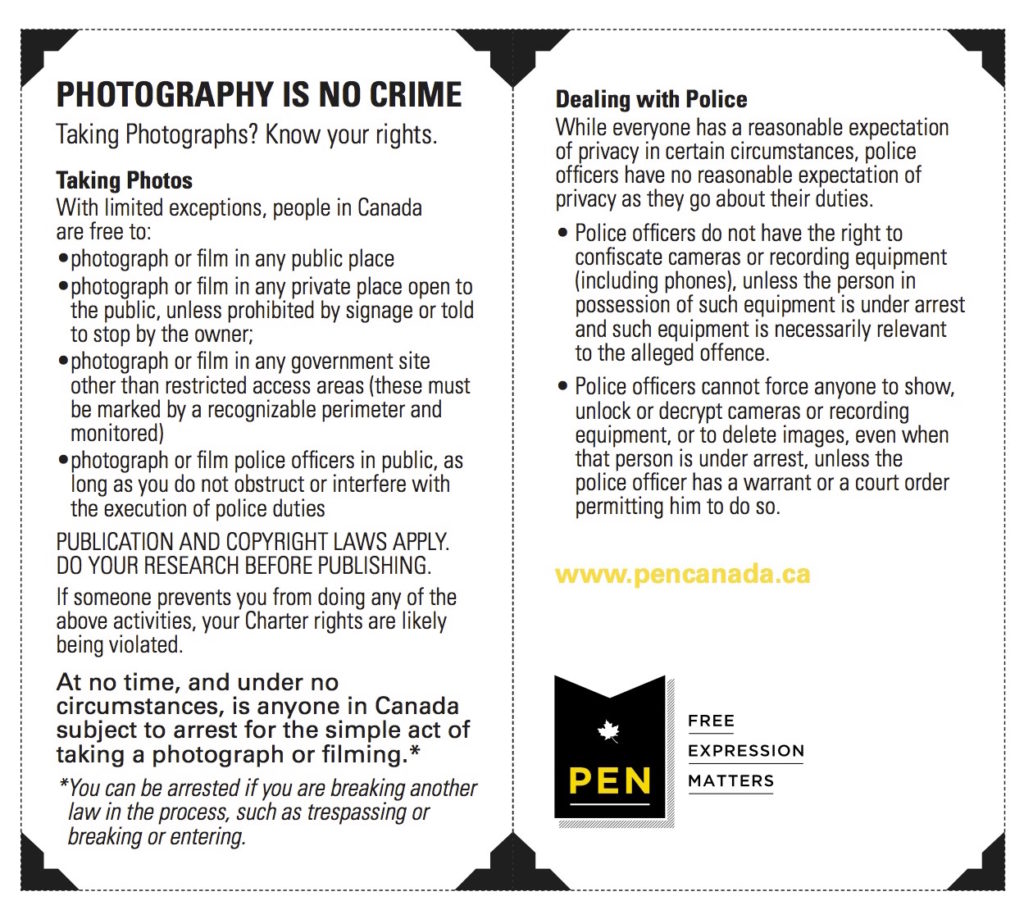

PEN Canada’s pocket guide to photography rights states that people in Canada have the right to “photograph or film in any public place.” Furthermore, police cannot “force anyone to show, unlock or decrypt cameras or recording equipment, or to delete images, even when that person is under arrest,” unless the officer has a warrant or court order.

Cell phone searches

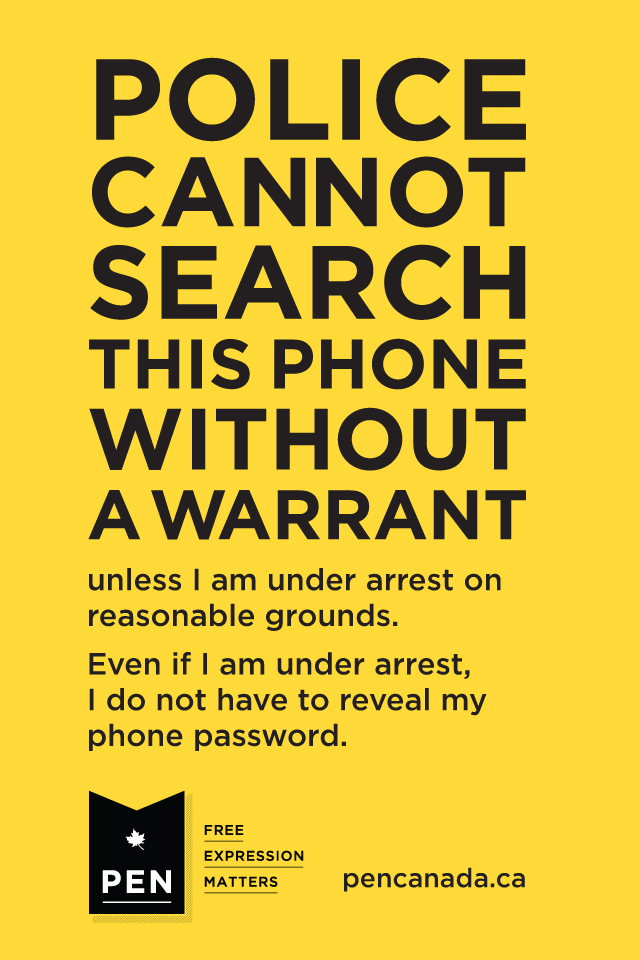

PEN has also produced a guide to cell phone searches in Canada, including the following downloadable phone wallpaper.

Recording

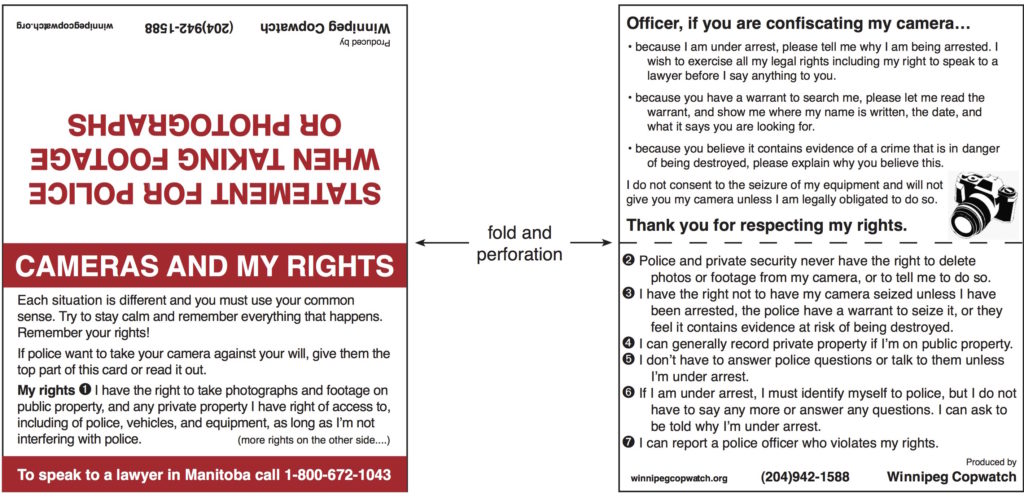

Winnipeg Copwatch produced a Know Your Rights card specific to recording. It states that as long as someone is not interfering with police, they have “the right to take photographs and footage on public property, and any property I have right of access to, including of police, vehicles, and equipment.”

Apps

An app created by Toronto lawyer Christien Levien, Legalswipe informs people of their rights during interactions with police officers. It also allows users to email video and audio to emergency contacts or upload it to Dropbox, to keep a copy of information in the event of an illegal camera search.

The Network for the Elimination of Police Violence (Toronto) has created an app called Cop Watch Video Recorder, which automatically uploads video to YouTube.

Rights on paper vs. rights in practice

If your rights are violated while recording the police, you may choose to make a complaint. The Canadian Civil Liberties Association has compiled a list of resources for making complaints against police in Canada. However, many oversight bodies have a poor track record for finding officers responsible and for disciplining them. In the report of the Independent Police Oversight Review released April 2017, a review of Ontario’s three civilian police oversight bodies, the Hon. Michael Tulloch found that during the consultation process, “virtually all stakeholders agreed that the current system for prosecuting and adjudicating public complaints is not working and fails to promote public confidence.”

Taking collective action are grassroots organizations like Black Lives Matter-Toronto and networks like the Toronto Police Accountability Coalition and the Network for the Elimination of Police Violence, which organize campaigns for police accountability and systemic change.